Whistling language canary islands: Whistled language of the island of La Gomera (Canary Islands), the Silbo Gomero – intangible heritage – Culture Sector

The Whisteling Language of La Gomera

A mysterious whistle from the past echoes in the mountains of La Gomera

Roque de Agando, La Gomera. Photo by Tamara Kulikova on WikimediaCommons.

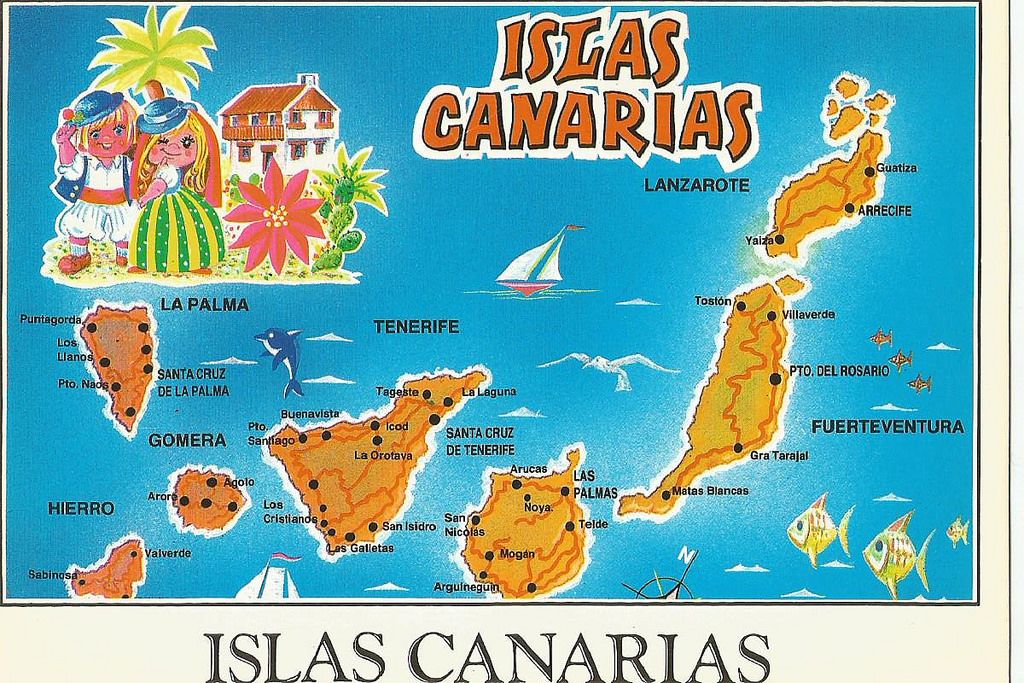

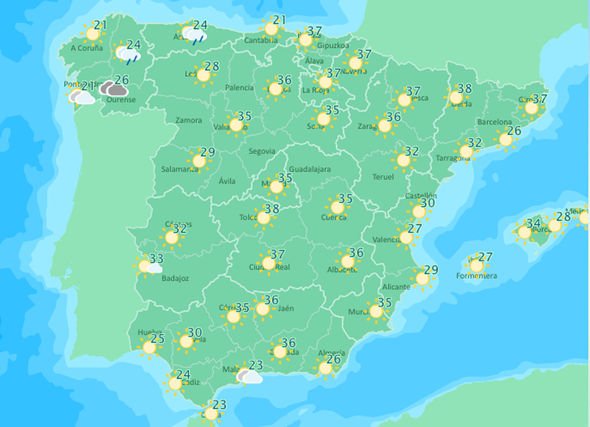

Mountain after mountain, valley after valley as far as the eyes can reach, this landscape keeps repeating itself infinitely. These emerald green mountains and valleys with their constantly repeating pattern make up the roller coaster-like Canarian landscape. The landscape itself holds the secret and reason behind why the whistling language developed here.

Without a direct way of communication due to the inaccessibility of the landscape, one can easily understand the need for a whistling language. It must have made daily life easier in a revolutionary way for the Guanches, the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands at the time.

Studies show that external communication, between the islands, was scarce due to insufficient knowledge of sailing. The internal communication, within an island, was also difficult because of the complexity and inaccessibility of the landscape, especially before the arrival of the whistling language.

San Sebastián de La Gomera. Photo by Bernhard1960 on Pixabay.

The Canarian whistling language or the “Silbo” is a tonal language, which is still practiced by many inhabitants in the Canary Islands today. The reason for the language is to be able to communicate with others over large distances, through mountains and valleys. The ones practicing the language are known as “whistlers”.

Practically, any language can be transformed into the Silbo, as it is translated into tunes recognisable from a distance.

From the beginning, it was used for the original language of the native inhabitants the “Guanches”. After the disappearance of the Tamazight or Canarian Berber it has come to be used with the Spanish language.

View of Teide from La Gomera. Photo by ravelinerin on Pixabay.

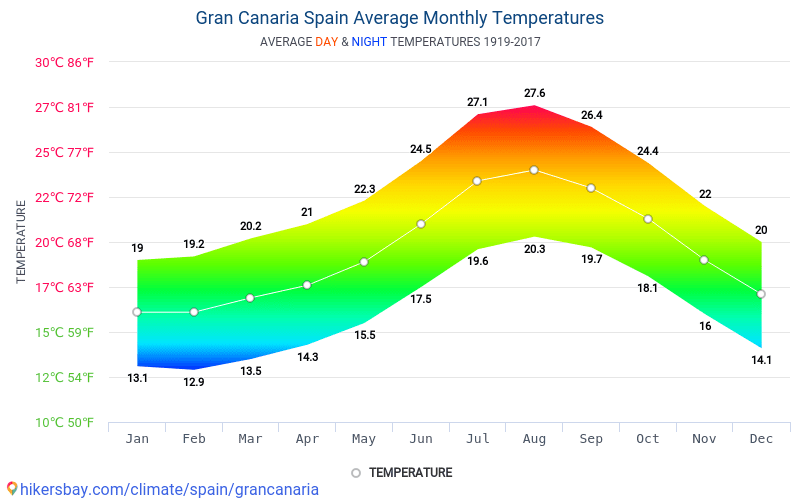

With the Silbo from La Gomera, it is possible to exchange messages in distances up to five kilometres! This whistling language uses six different sounds, two for vowels and four for consonants, with these sounds it’s possible to express more than 4.

There are also other whistling languages elsewhere. Some of these tonal languages have four sounds for vowels and four for consonants, thus a total of eight different sounds. Common for all these languages is that the sounds are approximates to the original language, variations are common and confusions possible.

There is very little information available about the original language of the Guanches, but we do know that it probably originated in North Africa.

Vallehermoso La Gomera. Photo by Tony Hisgett on Flickr.

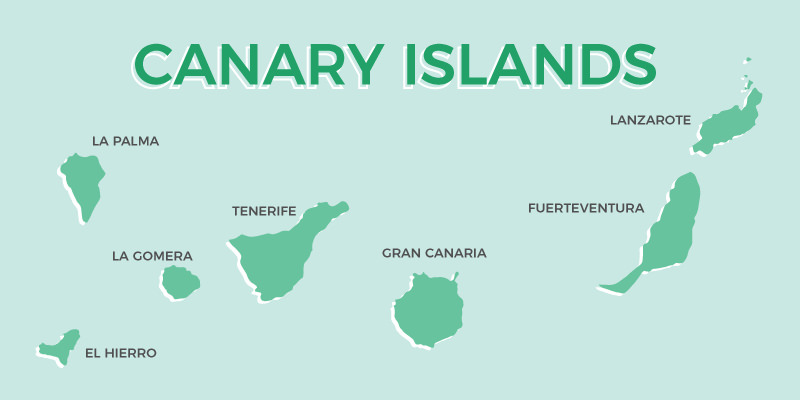

We also know that the whistling language was created by these native Canarians, as a tool of communication, and it was originally used in El Hierro, Tenerife, Gran Canaria and La Gomera.

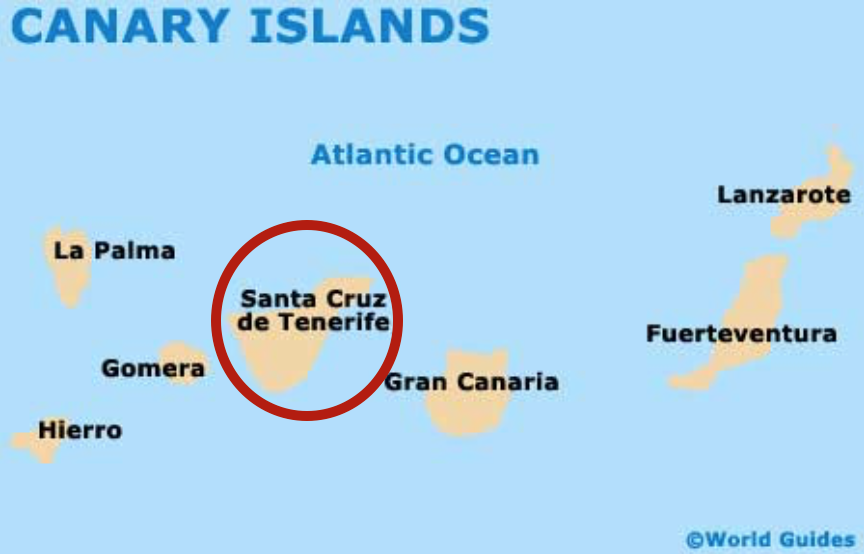

After the conquest of the Canarian archipelago in the 16th century, the last prehispánic natives in La Gomera finally adapted the Silbo to Spanish, the reason for this was most probably the extinction of their own language. The Silbo gradually disappeared from the rest of the island but still lives on in La Gomera, the second smallest island in the archipelago.

The whistling language had a much more profound impact here than on the rest of the islands and this proved to be the key to its survival.

Speaking of survival, in the 20th century with the arrival of mobile telephones and other ways of communication, in addition to emigration of the Gomeran population in search of a better life, there was a steep decline in the use of the whistling language.

In 1990 started a revitalization campaign led by the Canarian government including educational and legislative measures together with efforts of the population as a whole. These efforts resulted in great progress for the Silbo.

The government adjusted the education by adding the whistling to the educational system and making it compulsory, and in 1999 they also declared the Silbo patrimonial heritage. A decade later the Gomeran whistle gained world recognition when UNESCO registered it in the list of intangible cultural heritage.

Today, the whistling language is a mandatory subject in schools in La Gomera with at least one hour of class weekly.

Garajonay National Park, La Gomera. Photo by nike159 on Pixabay.

Did you know that on average, around 25 languages disappear each year? Check out Andawn F.’s story to learn more fun facts about world languages.

Have Fun with Languages

If you love learning foreign languages too

medium.com

As per the report of UNESCO in 2009, a big majority of the population in La Gomera understands the whistling language, especially those born before 1950 as well as students attending school from 1999 onward.

The Silbo in La Gomera coexists with other tonal languages in the world, including those of Evian, an island in Greece and Kuskoy, in the east of Turkey and in the French Pyrenees. Nevertheless the “Gomeran whistle” is the only tonal language to have been studied thoroughly, as well as the one with most practicants.

Tonal languages are interesting from the point of view of being simple ways of communication; it makes it possible for us to study how a language first appears and then how languages develop in general.

The recognition and prestige the Gomeran Silbo has gained in the last years have had unexpected consequences. There are even competitions between native whistlers in Gomera to gain tourists’ attention.

We can finally conclude that the efforts of revitalization of the Silbo in La Gomera have been highly successful. Until now the Silbo has been passed on from generation to generation, we surely hope that it will continue that way and that we might be able to discover even more of the Guanches secrets!

The Fascinating Whistled Languages of the Canary Islands, Turkey & Mexico (and What They Say About the Human Brain)

For some years now linguist Daniel Everett has challenged the orthodoxy of Noam Chomsky and other linguists who believe in an innate “universal grammar” that governs human language acquisition.

In places as far flung as the Brazilian rainforest, mountainous Oaxaca, Mexico, the Canary Islands, and the Black Sea coast of Turkey, we find languages that sound more like the speech of birds than of humans. “Whistled languages,” writes Michelle Nijhuis in a recent New Yorker post, “have been around for centuries. Herodotus described communities in Ethiopia whose residents ‘spoke like bats,’ and reports of the whistled language that is still used in the Canary Islands date back more than six hundred years.

In the short video from UNESCO at the top of the post, you can hear the whistled language of Canary Islanders. (See another short video from Time magazine here.) Called Silbo Gomero, the language “replicates the islanders’ habitual language (Castilian Spanish) with whistling,” replacing “each vowel or consonant with a whistling sound.” Spoken (so to speak) among a very large community of over 22,000 inhabitants and passed down formally in schools and ceremonies, Silbo Gomero shows no signs of disappearing. Other whistled languages have not fared as well. As you will see in the documentary above, when it comes to the whistled language of northern Oaxacan peoples in a mountainous region of Mexico, “only a few whistlers still practice their ancient tongue.” In a previous Open Culture post on this film, Matthias Rascher pointed us toward some scholarly efforts at preservation from the Summer Institute of Linguistics in Mexico, who recorded and transcribed a conversation between two native Oaxacan whistlers.

Whistled languages evolved for much the same reason as birdcalls—they enable their “speakers” to communicate across large distances. “Most of the forty-two examples that have been documented in recent times,” Nijhuis writes, “arose in places with steep terrain or dense forests—the Atlas Mountains, in northwest Africa; the highlands of northern Laos, the Brazilian Amazon—where it might otherwise be hard to communicate at a distance.” Such is the case for the Piraha, the Canary Islanders, the Oaxacan whistlers, and another group of whistlers in a mountainous region of Turkey. As Nijhuis documents in her post, these several thousand speakers have learned to transliterate Turkish into “loud, lilting whistles” that they call “bird language.” New Scientist brings us the example of whistled Turkish above (with subtitles), and you can hear more recorded examples at The New Yorker.

As with most whistled languages, the Turkish “bird language” makes use of similar structures—though not similar sounds—as human speech, making it a bit like semaphore or Morse code. As such, whistled languages are not likely to offer evidence against the idea of a universal grammar in the architecture of the brain. Yet according to biopsychologist Onur Güntürkün—who conducted a study on the Turkish whistlers published in the latest Current Biology—these languages can show us that “the organization of our brain, in terms of its asymmetrical structure, is not as fixed as we assume.”

Where we generally process language in the left hemisphere and “pitch, melody, and rhythm” in the right, Nijhuis describes how the whistled Turkish study suggests “that both hemispheres played significant roles” in comprehension. The opportunities to study whistled languages will diminish in the years to come, as cell phones take over their function and more of their speakers lose regional distinctiveness.

via The New Yorker

Related Content:

Speaking in Whistles: The Whistled Language of Oaxaca, Mexico

How Languages Evolve: Explained in a Winning TED-Ed Animation

Noam Chomsky Talks About How Kids Acquire Language & Ideas in an Animated Video by Michel Gondry

What Makes Us Human?: Chomsky, Locke & Marx Introduced by New Animated Videos from the BBC

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Whistles are words to brains of those who speak special ‘language’

Archive

January 6, 2005

The human brain’s remarkable flexibility to understand a variety of signals as language extends to an unusual whistle language used by shepherds on one of the Canary Islands off the northwest coast of Africa.

And the way the brain processes these whistles is similar to the way it goes about deciphering English, Spanish or other spoken languages, according to research being published in this week’s issue of the journal Nature.

“Science has developed the idea of brain areas that are dedicated to language and we are starting to understand the scope of signals that can be recognized as language,” said David Corina, a UW associate professor of psychology and co-author of the study.

“But how far can you stretch this idea? Sign language studies have shown we can stretch the envelope and here we are expanding it in another way to a whistle language. The brain is adaptable, or plastic, in understanding a variety of forms of communication.”

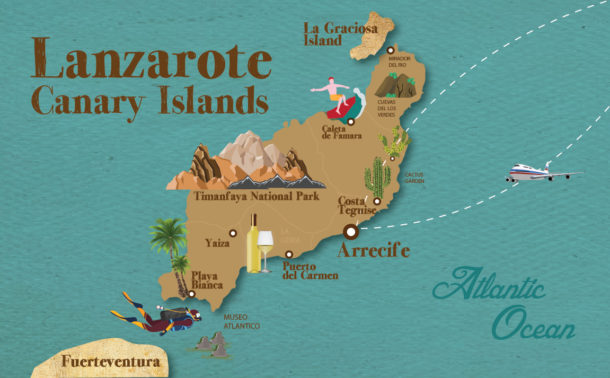

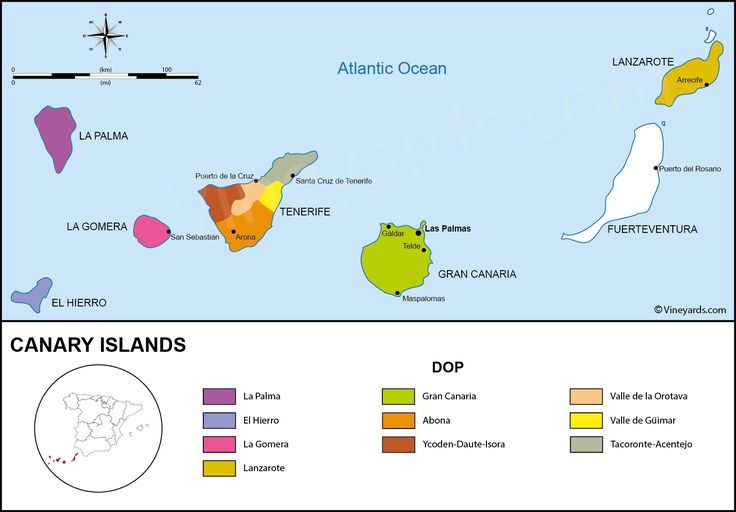

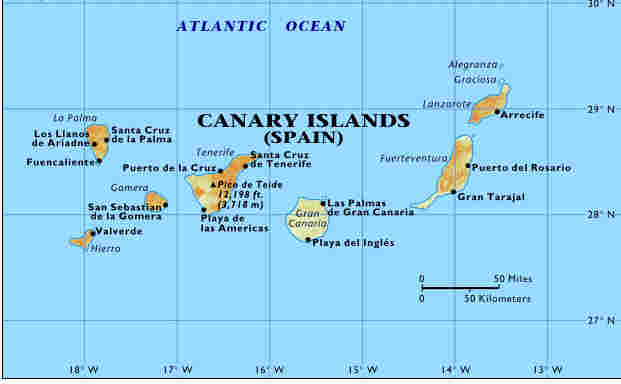

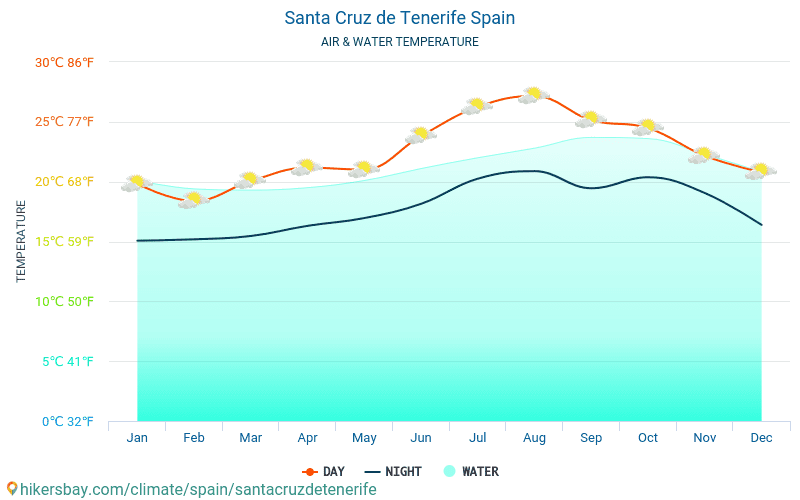

The language studied by Corina and his colleague, Manuel Carreiras, a psychology professor at the University of La Laguna, on the island of Tenerife in the Canaries, is Silbo Gomero, or Silbo. It is primarily used by shepherds to communicate with each other over long distances of rugged terrain on the island of La Gomera, another island in the Spanish owned Canaries.

To see how the brain processes Silbo, the researchers recruited five silbadors, or speakers of Silbo, who also were fluent in Spanish and five Spanish speakers who did not understand Silbo. The word silbador comes from the Spanish verb silbar, which means to whistle.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging was used to measure brain activation, or activity, during two tasks. The two groups first were given a passive listening task in which they listened to recorded sentences in Spanish and Silbo and were to keep track of what had been said. In the second task, the subjects listened to blocks of Spanish words for colors or animals and the equivalent “words” in Silbo. Individual recorded words were played once every three seconds. While having their brains scanned, the subjects were asked to keep track of how many times a target word or whistle appeared during a trial.

When the silbadores listened to the Silbo sentences, several regions were activated in the left hemisphere of their brains including ones in the posterior temporal-parietal region and the frontal premotor cortex.

Both the silbadores and the Spanish speakers showed this pattern of bilateral activation when they listed to Spanish sentences. However, the results were different when the Spanish speakers listened to the Silbo sentences. Several brain regions were activated, but none has been specifically implicated in language processing, indicating they did not recognize Silbo as a language, Corina said.

The researchers found a similar pattern during the second tasks. While both subjects groups were able to detect the target whistle sound, only the silbadores showed bilateral brain activity in the language center. Data from both tasks showed a common focus of brain activity near the temporal-parietal junction among the silbadores.

“Our results provide more evidence about the flexibility of human capacity for language in a variety of forms,” said Corina.

Silbo is believed to have been brought to the island by Berbers from North Africa and today is a surrogate language for Spanish. It condenses Spanish into two vowels and four consonants.

“You wouldn’t call Silbo a full-fledged language. Children are not born whistling it,” Corina said. “In general, anything in Spanish can be translated into Silbo, but context is very important.”

Silbo is an occupation-centered language and is used to say such things as “open the gate” or “there is a stray sheep.” It is not the world’s only whistle language. There are others in Greece, Turkey, China and Mexico, according to Corina.

The research was funded by Cabildo de La Gomera, the Spanish Ministry of Education and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology. Co-authors of the paper were Jorge Lopez of IMETISA, Hospital Universitario de Canarias in Tenerife, and Francisco Rivero of the University of La Laguna.

Hear Silbo Gomero:

Silbo for “John milked the goats”:

http://www.uwnews.org/relatedcontent/2005/January/rc_parentID7171_thisID7263.wav

Silbe for “Domingo is sick”:

http://www.uwnews.org/relatedcontent/2005/January/rc_parentID7171_thisID7264.wav

Sing like a canary! The whistling consultant who taught Romanian noir gangsters a tune | Film

Try to imagine the least film-noir scene possible and you might come up with a group of five-year-olds learning to whistle. It is late morning, pre-lockdown, in a classroom at Nereida Díaz Abreu school on La Gomera in the Canary Islands, and the teacher – a bent knuckle crammed in his mouth – is relaying instructions in a piercing, swooping, set of whistles.

“Touch your left ear with your right hand,” the teacher reiterates in Spanish.

“Ay-ay-ay!” the children hoot in disbelief.

They are learning the el silbo gomero, the island’s whistling language, which dates back at least to the 15th century and is now the unlikely star of a new Romanian film noir, The Whistlers. A bent Bucharest cop Cristi (Vlad Ivanov) is summoned to the distant island by a local drug gang to learn their secret language, so he can help them retrieve €30m stolen by their eastern European middleman. It is a rich, roundabout handbook on the subtleties of communication; even the film’s structure, a series of flashbacks in which you are perpetually looking for who is double-crossing whom, seems to collude in this.

With its deep-cut volcanic ravines, shaggy Tolkienian laurel forest and Tenerife’s volcano floating above the cloudline, La Gomera hits the visual jackpot.

Contrary to film noir’s most famous whistling tip, from Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not – “You just put your lips together and blow” – el silbo takes some mastering. The film’s silbo consultant, Kico Correa, insisted the lead actors had to learn for real. “It’s been classified as Unesco World Heritage, so it needs to be treated with special respect,” he explains to me at a harbourside cafe. “You can dub the sound, but the lip movements needed to be credible.

Ivanov and Catrinel Marlon, who plays the film’s moll, Gilda, were both put on to a two-week silbo crash course in Bucharest, followed up later with Skype sessions. It was not simply a case of training in the physical mechanics, but also how to understand its system of letter substitution. It strips down an underlying language – Spanish, in La Gomera’s case – to just two vowels and four consonants. The same approximate whistling pitch, for example, is used for “A”, “O” and “U”. Rephrasings, clarifying questions and awareness of the context at hand are sometimes needed to avoid misunderstandings.

Even though the actors’ whistling was eventually dubbed by the island’s silbo teachers, Correa gives them A for effort. Marlon, who started slightly later than Ivanov, had more natural aptitude, he says. A fashion model, she whistled so hard during practice that she had to pull out of a photoshoot in Italy because her lips were too chafed.

Porumboiu lasted just a single day on the course because he was busy preparing the film.

It is there in his debut 12:08 East of Bucharest, with its radio show guests bickering about how the exact moment the news of Ceauşescu’s deposal was relayed to their backwater town is crucial to deciding whether it can be said an actual revolution took place there. Or the police captain played by Ivanov in Police, Adjective, who turns to the dictionary for the definition of his profession to solve a crisis of conscience. Or the bureaucrat in Porumboiu’s last film, Infinite Football, whose tinkering with the rules of the sport doesn’t pan out in reality. The director wrings out a colourful stream of comic possibility from misinterpretation in these films, but language, via el silbo, plays a darker, concealing role in The Whistlers, a world in which people can rarely express themselves truthfully.

The director, speaking on the phone under lockdown in the Romanian countryside, is at a loss to explain his interest in the theme. “To be honest, I’m not doing it on purpose. It’s a personal matter, this feeling that we don’t understand each other.” Where does it come from? “I think it’s coming from … my inability … ” He tails off.

We say to the kids: when you go to Tenerife and say you’re from La Gomera, people will ask you if you can whistle

Kiko Correa

Back in March on La Gomera, I am having my own communication issues. Five minutes of efforts better described as spitting than whistling are enough to leave my deoxygenated head spinning. But Correa – a short, calm Gomero who resembles Robert Forster – has had to learn patience in his day job organising the island’s silbo syllabus. The language had virtually died out in the 1970s, associated with a peasant lifestyle many people were keen to leave behind. Correa’s parents were among a minority who didn’t view it as backward.

El silbo’s moment came in the late 90s, when an upsurge in interest resulted in a push to make it compulsory on the school curriculum. Now learning it for half an hour each week is obligatory for six-year-olds and upwards; three- to five-year-olds also receive tuition, mostly in comprehension. “We don’t make a big effort to say: ‘You should learn it to support your culture,’” says Correa. “It’s too much weight for kids. We encourage them to do it for fun. We say: ‘When you go to Tenerife and say you’re from La Gomera, people are going to ask you if you can whistle.’”

I also sit in on an impressively adept classroom of teenagers, chattering away in silbo like manic songbirds. But how much do they use it in everyday life? Marta, a regular victor in the class’s silbo competitions, says: “Sometimes.

The education programme is vital for preserving this rare offshoot of the world linguistic tree. But from the silence reigning over La Gomera’s stepped basalt cliffs, where there are few shepherds now, it is clear that it’s not quite a living language, either; it’s mostly heard in classrooms or in restaurants, in demonstrations for tourists.

While The Whistlers is unlikely to make the island’s hills suddenly alive with the sound of unusually articulate birds, it should help magnify el silbo’s worldwide cultural status. Correa appears briefly in the film as a Gomero gangster, but was originally slated for a bigger part as the teacher; as Porumboiu learned more about the language and the role expanded, it called for a professional actor.

The Whistlers and Infinite Football will stream from 8 May in the UK and Ireland on Curzon Home Cinema

– IELTS is fun to learn

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

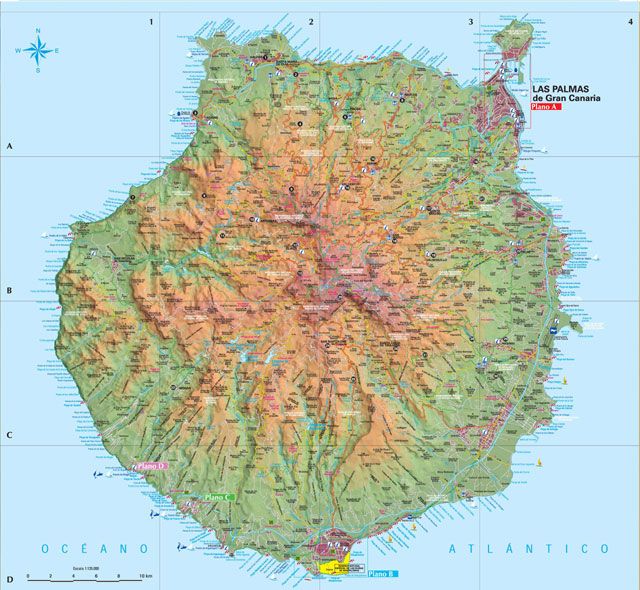

La Gomera is one of the Canary Islands situated in the Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of Africa. This small volcanic island is mountainous, with steep rocky slopes and deep, wooded ravines, rising to 1,487 metres at its highest peak (Q14). It is also home to the best known of the world’s whistle ‘languages’, a means of transmitting information over long distances which is perfectly adapted to the extreme terrain of the island.

This ‘language’, known as ‘Silbo’ or ‘Silbo Gomero’ – from the Spanish word for ‘whistle’ – is now shedding light on the language-processing abilities of the human brain, according to scientists. Researchers say that Silbo activates parts of the brain normally associated with spoken language, suggesting that the brain is remarkably flexible in its ability to interpret sounds as language.

‘Science has developed the idea of brain areas that are dedicated to language, and we are starting to understand the scope of signals that can be recognised as language,’ says David Corina, co-author of a recent study and associate professor of psychology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Silbo is a substitute for Spanish, with individual words recoded into whistles which have high- and low-frequency tones (Q20). A whistler – or silbador – puts a finger in his or her mouth to increase the whistle’s pitch (Q21), while the other hand can be cupped to adjust the direction of the sound (Q22).

The silbadores of Gomera are traditionally shepherds and other isolated mountain folk, and their novel means of staying in touch allows them to communicate over distances of up to 10 kilometres. Carreiras explains that silbadores are able to pass a surprising amount of information via their whistles. ‘In daily life they use whistles to communicate short commands (Q23), but any Spanish sentence could be whistled.’ (Q15) Silbo has proved particularly useful when fires have occurred on the island and rapid communication across large areas has been vital (Q24).

The study team used neuroimaging equipment to contrast the brain activity of silbadores while listening to whistled and spoken Spanish.

‘Our results provide more evidence about the flexibility of human capacity for language in a variety of forms,’ Corina says. ‘These data suggest that left-hemisphere language regions are uniquely adapted for communicative purposes, independent of the modality of signal. The non-Silbo speakers were not recognising Silbo as a language. They had nothing to grab onto, so multiple areas of their brains were activated.’

Carreiras says the origins of Silbo Gomero remain obscure, but that indigenous Canary Islanders, who were of North African origin, already had a whistled language when Spain conquered the volcanic islands in the 15th century (Q17).

But with modern communication technology now widely available, researchers say whistled languages like Silbo are threatened with extinction (Q25). With dwindling numbers of Gomera islanders still fluent in the language, Canaries’ authorities are taking steps to try to ensure its survival.

Questions 14-19

14 La Gomera is the most mountainous of all the Canary Islands. NOT GIVEN [Locate]

15 Silbo is only appropriate for short and simple messages. FALSE [Locate]

16 In the brain-activity study, silbadores and non-whistlers produced different results. TRUE [Locate]

17 The Spanish introduced Silbo to the islands in the 15th century. FALSE [Locate]

18 There is precise data available regarding all of the whistle languages in existence today.

19 The children of Gomera now learn Silbo. TRUE [Locate]

Questions 20-26

Silbo Gomero

How Silbo is produced

● high- and low-frequency tones represent different sounds in Spanish 20…words… [Locate]

● pitch of whistle is controlled using silbador’s 21…finger… [Locate]

● 22…direction… [Locate] is changed with a cupped hand

How Silbo is used

● has long been used by shepherds and people living in secluded locations

● in everyday use for the transmission of brief 23…commands… [Locate]

● can relay essential information quickly, e.g. to inform people about 24…fires… [Locate]

The future of Silbo

● future under threat because of new 25…technology… [Locate]

● Canaries’ authorities hoping to receive a UNESCO 26…award… [Locate] to help preserve it

Whistled Languages Around The World

What’s in a whistle? Entire worlds, for one.

What’s Up With Whistled Languages?

As far back as the 5th century B.C., the Greek historian Herodotus described cave-dwelling Ethiopians whose “speech is like no other in the world: it is like the squeaking of bats.”

Whistled languages have historically almost always originated in remote, mountainous villages or dense forests, where environmental conditions required a method of communication that could travel over long distances. Whistles don’t echo as much as shouts, which means they’re less likely to get distorted or scare away potential prey. They also require less exertion on the part of the speaker, and they can travel up to 10 kilometers (just over 6 miles) in some cases, which is many times farther than shouts, thanks to the narrow, high-pitched frequency of the sound.

Julien Meyer, a researcher at the University of Grenoble in France, has studied whistled languages extensively, and he hypothesizes that whistling might have been a precursor to spoken language. This is not altogether different from a theory proposed by Charles Darwin that singing and whistling both formed a sort of “musical protolanguage.”

One thing that’s important to understand about whistled languages is that they’re always based on the local spoken language. According to Meyer, regions of the world where “tonal” languages exist, like in Asia, tend to produce whistled languages that replicate the melodies of the spoken sentences. Other languages, like Spanish and Turkish, produce whistled versions that imitate the various changes in resonance that accompany different vowel sounds, with consonants conveyed by abrupt shifts from note to note.

Additionally, whistled tongues have revealed surprising information about the way our brain processes language.

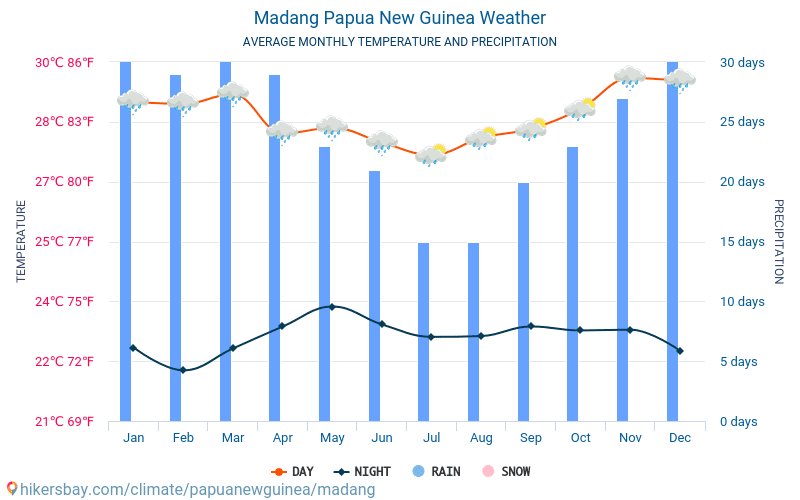

Most interesting of all, though, are the very human stories they tell — from the Canary Islands to the Amazon, the Laotian highlands, the Atlas Mountains, Papua New Guinea, the Bering Strait, the Pyrenees, and back again.

Kuşköy’s Bird Language

Up in the mountains of Northern Turkey, in the Çanakçı district of Giresun, there’s a single village, Kuşköy, where whistled languages still persist (to a degree). Though the bird language had once been prevalent throughout the mountainous region, it’s mostly spoken only by shepherds today, and text messaging has threatened its total extinction.

No longer passed down to younger generations, most living speakers are aging. Among the youth who do learn it, it’s more often the men who learn it as a matter of pride.

Turkey’s “bird language” was recently recognized by UNESCO and added to its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding.

Antia’s Sfyria

In the small village of Antia, tucked away on the inclines of Mount Ochi on the Greek island of Evia, the residents whistle a language known as sfyria. For thousands of years, the language has been passed down through the generations of shepherds and farmers. According to some residents, the language either came from Persian soldiers hiding in the mountains roughly 2,500 years ago, or from the Byzantine era, when locals needed a cryptic way to warn each other of danger. Some say that whistlers from Antia would act as sentries in the times of ancient Athens to warn of attack against the empire.

The story of sfyria is similar to the story of Turkey’s bird language, in that the remaining speakers are all aging out, in some cases losing their teeth (and their ability to make the sounds).

The word “sfyria” comes from the Greek sfyrizo, or “whistle,” but its use transcends the needs of empire and agriculture. One resident told the following story to the BBC: “One night, a man was in the mountains with his sheep when it started snowing. He knew that somewhere deep in the mountains there was a beautiful girl from Antia with her goats. So he found a cave, built a fire and whistled to her to come keep warm. She did, and that’s how my parents fell in love.”

In the above documentary, Dr. Mark Sicoli, assistant professor of Linguistics at Georgetown University, studies the whistled Chinantec language.

San Pedro Sochiapam’s Chinantec

In Oaxaca, Mexico, the village of San Pedro Sochiapam is where the Chinantec people live among mountainside cornfields and hilly footpaths.

The Chinantec language, which has been around since pre-Hispanic times, can account for past and future tense and reach distances of up to 1 kilometer (about two-thirds of a mile).

But here, as with everywhere else, the need for whistled language is declining, which means there is only a handful of people left who are still proficient in this tongue. This is partly owing to a lack of interest among younger generations, but also partly to a decline in coffee production, which once made up more than 30 percent of the state’s exports. That, and people seem more inclined to use cellphones and walkie-talkies these days.

La Gomera’s Silbo

In the Canary Islands of Spain, whistled language is said to have originated among the North African inhabitants prior to the arrival of the first European settlers in the 15th century. When the Spanish came, the natives adapted their whistling language to more closely resemble Spanish.

Back in the day, when whistling was a matter of necessity, the locals would whistle to each other to avoid the Guardia Civil, who would come to pick them up when the mountain caught fire, often using them as unpaid labor to extinguish the blaze.

UNESCO’s short documentary on the Silbo language of La Gomera.

Himalayan H’mong

In the foothills of the Himalayas, the H’mong people use whistled language in farming and hunting contexts, but they also use it as a form of courtship.

Though rarely deployed in this manner nowadays, the whistled language would be used by boys who wandered through nearby villages in the past, whistling their favorite poems. In some cases, a girl might respond, and the two might begin flirting with each other in this manner.

According to the BBC, the romance of this ritual is heightened by the fact that whistling is much more anonymous than speaking, and some couples might create their own personal codes (like Pig Latin, but for whistling). This creates a sense of privacy in what is otherwise a very public exchange.

What are whistling languages and who speaks them – Knife

The first mention of whistling languages is found in the “History” of Herodotus, dated to the 5th century BC. e. “Their speech is unlike any other in the world: it resembles the squeak of bats” – this is how he described the cave dwellers of Ethiopia. There is no reliable data on exactly which tribes communicated in this way, but whistling languages can still be heard in the Omo Valley in Ethiopia.

In ancient Chinese texts dated to the 8th century A.D. e, there is a description of a Taoist practice, the name of which can be translated as “Principles of whistling.” This is one of the earliest works on phonetics: it describes what exercises you need to do to learn how to whistle correctly, and also gives twelve specific whistling techniques, with instructions on the location of the tongue and lips, breath control, etc. It was believed that whistling poetry immerses a person in a meditative state. Whistling communities of the Hmong and Akha still exist in southern China.

The first indisputable historical evidence for the existence of a sibilant form of the tongue is found in the work of two Franciscan priests who accompanied the French explorer Jean de Bethencourt, who went to conquer the Canary Islands in 1402.

In their diary, published under the title “The Canary”, the priests Bontier and Le Verrière mention that the inhabitants of the islands spoke “with two lips, as if they had no tongue.”

Later research revealed that they encountered a whistling form of the Berber language.

In the Americas, the earliest evidence of the practice of whistling comes from 1755, when a Jesuit historian reported a whistling form of speech among the Aigua people of Paraguay: “They use a language that is difficult to learn because they whistle rather than talk.”

This property – the difficulty of learning whistled languages by those not accustomed to people outside the community – was later exploited in military operations.

As you can see, whistling languages have existed for a long period of history and have been manifesting all over the world. Can this unusual form of communication, in which language and musicality are intertwined, help us learn more about the origins of language? Charles Darwin suggested the existence of a kind of “proto-language of music”. According to this view, people began to sing even before they could speak, perhaps as a kind of courtship ritual.

Like birds, people could demonstrate their virtuosity, strengthen social bonds and scare off rivals, even if the whistle did not carry practical information.

However, over time, this practice would lead us to more precise control of the vocal cords, which would lay the foundation for more meaningful utterances.

One of the most respected researchers in the field of whistling languages, Julien Meyer, suggests that whistling was one of the stages in the development of language that pushed people to more complex communication. He notes that while non-human primates cannot learn to speak, some have learned to whistle.

Bonnie, an orangutan at the National Zoo in Washington, DC, has learned to imitate the simple melodies of her caretaker Erin Stromberg, and wild orangutans have adapted to emit a high-pitched whistle by sucking air through a leaf.

Such manifestations suggest that whistling requires less effort than speech, making it an ideal stepping stone on the path to language. If this is true, then whistling signals may have started as a musical proto-language, and as they became more complex and filled with meaning, they turned into a way to coordinate hunting.

Meyer’s research suggests that whistling was a distinct survival advantage for our ancestors: they could communicate at a distance without attracting the attention of predators and prey.

Recognition and learning

It must be understood that whistling languages are not separate units, but rather other forms of habitual languages. Only the form of communication is subject to change – the voice register of speech – and the semantic content remains the same. Thus, whistling speech is a phonetic adaptation of natural language that has appeared for communication over long distances, when it is not possible to see eye to eye or the natural features of the landscape do not allow this.

The principle of whistling speech is simple: while whistling, people syllable by syllable simplify and transform familiar words into whistling melodies.

Whistlers even emphasize that they whistle exactly as they think in their own language, and that the whistling messages they receive are instantly interpreted as ordinary speech.

Another important feature that distinguishes a whistle from a whisper or shout is its illegibility for people from the outside. It cannot be called completely unique – in the end, even in your own language, it can be difficult to make out operatic singing. But in the case of a whistle, people often perceive it not as communication, but rather as a joke. Perhaps it is this aspect of secrecy that has allowed whistling languages to “survive” for so long. At the same time, this mystery significantly limited possible research: whistling languages were discovered by chance, and the number of speakers decreases every year.

Learn to whistle just like any other language. Children subconsciously get used to whistling speech signals if they hear them often enough, but they take a little longer to master. A child who speaks at 3 or 4 years old understands whistling language at 5-6 years old, but does not master it well enough until 10-12 years old.

Whistling languages, although found on many continents, persist only in remote or isolated communities.

They are not limited to a particular territory, language family or structure. Depending on the features of the landscape, patterns of communication are formed: for what needs the whistle is used and what technique the locals choose.

In the forests of Portugal and Brazil, they usually whistle during hunting. As a rule, people are not very far from each other, lips and hands are used for whistling. In the case of Mexican mountains with dense forests, locals coordinate farming: distances become longer, and lips and teeth are used for communication.

If we talk about sheer cliffs with sparse vegetation in Greece, Turkey, Spain or Africa, then shepherding prevails there, the distances are very large, and for whistling they resort to the help of fingers.

Examples of whistling languages

As of 2018, there were about 70 whistled languages in the world. The most famous and studied habitat of the whistling community was La Gomera, one of the non-tourist Canary Islands. Silbo Gomero was the first of the whistled languages to receive the status of a living heritage of UNESCO, it also has the largest number of speakers – about 20 thousand.

The Silbo Homero language now plays an important role in the daily life of the island. It is taught in schools, it is used to attract the attention of tourists – in some restaurants, waiters transmit order details by whistling.

Teenagers sometimes earn extra money and put on a whole show for visitors, managing to adapt the whistle for other languages. However, since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, such practices have had to be abandoned – putting fingers in your mouth has become unsafe. Now schoolchildren do not practice whistling themselves, but listen to recordings.

The older generation notes that it is more difficult for them to understand young people who learn to whistle in school, and not in pastures. For them, such a whistle is too elegant and precise, and the vocabulary is richer and more diverse. Elderly residents of the island of La Gomera recall using silbo to warn locals of the arrival of the police. In Corneliu Porumboiu’s recent Romanian thriller The Whistlers, silbo is used as a secret code language by gangsters.

On the Greek island of Euboea, in the village of Antia, Sefirian is spoken, the sound of which resembles the sounds of birds. Sefiriya is one of the most endangered and rare languages in the world.

Now the population of the village is 37 people, but most of them have lost their teeth, so they cannot whistle. In 2018, only 6 people spoke Sefirian fluently. Local residents are doing their best to preserve their language – they organize classes, write to the local administration with a request to open a school, and invite scientists to record the sound of the language. Scholars learned about the Sefirian language only in 1969, when a plane crashed in the mountains near Antia. Members of the search party heard the shepherds speaking in a whistling language. The range of communication in Sefirian can reach 4 kilometers.

In Mexico, Sochiapan Chinantec and Mazatec are used for whistling. The theoretical range of whistling can reach two kilometers, but the inhabitants prefer to communicate over short distances and for them it is more a way of socialization, and not a forced tool.

Mexican communities use whistles to talk in the market, a situation unique to whistling languages.

In the north of Turkey, in the village of Kusköy, they speak the “language of birds”. It has been used in this area for many centuries and has about 10,000 speakers. In 2017, along with silbo gomero, it was included in the UNESCO list of oral and intangible cultural heritage in need of protection. Every year, the village hosts a festival dedicated to the traditions, history and culture of bird language. Recently, they began to study it at the elementary school and the Turkish University of Giresun at the Faculty of Tourism.

The Hmong people, who live in the foothills of the Himalayas in Vietnam, have their own version of a whistling language used by hunters and farmers. However, it also has another popular use – the language of courtship. Although rarely practiced today, young people used the whistling Hmong language as a language of flirtation.

***

The rapid development of technology has significantly reduced the need for whistling, but network coverage is still faltering in high mountainous areas. Elderly residents of whistling communities try to pass on their knowledge to young people, participate in festivals dedicated to language traditions and often ignore mobile phones, preferring to communicate in a proven way. Adolescents resort to whistling much less often, but still periodically train and are interested in the ancient skill. For them, this is a way to get closer to history and understand the origins of local traditions. Another important feature of whistling comes in handy from time to time – this way you can quickly convey information that is not intended for other people’s ears. One way or another, whistling tongues remain a unique phenomenon, many mysteries of which have yet to be solved.

Whistle Language – Language Heroes Library

“For me, words are not letters or sounds,” – used to sing Polad Bulbul ogly .

Well, if we understand a “word” as a set of some elements that has a certain meaning, then, indeed, neither letters nor sounds are mandatory. Well, there is Morse code, semaphore alphabet, smoke and fire signals , knot letter finally numbers. And the type of languages, which we are talking about below, does not have letters and in general does not have any graphics, but there are sounds, and all of them are whistling, and not just some consonants. It is not readable, but it sounds, and how! Let’s talk about whistling tongues .

Canary Islands

PictureCredit

On an island named Homera there is a language Silbo Homero or el silbo , which simply means “whistling”.

Tourists from different countries are brought to a restaurant and demonstrated how “whistling” sounds from the lips of native speakers – silbadors . But not only. So the melody and rhythm of have not only the words of Spanish, but also of any other language, local virtuosos will whistle the French “merci” as “fufi” and “good afternoon” as “FIOFIFIFE” .

Mineral water bottle turns in “fyufifya fyifyafyafya fyofi”

Canary and canary whistle across the hall like canaries.

But this is not only a lure and entertainment for foreign tourists, this “bird language” is a masterpiece of cultural heritage UNESCO , studied in local schools, and even used in practice among the mountains and hills, where it actually originated.

The practical meaning of this trill for high landscapes is rather mundane – to invite someone to your place, to report danger, to ask for help, to announce one’s presence.

True, the cellular communication that has reached these places makes the “nightingale code” somewhat redundant. And it is all the more important to preserve this tradition and let it whistle like a bullet in the air and disappear.

Turkey

PictureCredit

Canarians are not alone in this world who have developed a system of whistling.

Turks in the village Kushköy also whistle to each other from hill to hill.

Their language is called Kush Dili and belongs to a variety of the Turkish language, that is, to the Turkic group, while Silbo Homero belongs to the Romance.

And yes, Kush Dili is also on the UNESCO list.

Just whistle – he will appear

Whistling tongues are obviously not intended for long philosophical conversations, but calling someone to check if everything is in order is easy! Or ask a neighbor on the opposite mountain if he can visit in the evening or not.

The functions of the Turkic whistle are the same as those of the Canarian – to call, ask, to “talk” about something, about the number of bags needed, for example. Both whistling languages arose as a result of the same needs of the inhabitants of different regions with a similar landscape. No one “whistled” this idea from anyone.

And the problem of preservation is equally acute in both languages.

Although, “both” is not entirely accurate, because whistling, if not of the entire language, but of a certain lexicon, is present in the Yoruba languages , Pirahana it is they who communicate by whistling.

It is really difficult to understand the interlocutor, because the “musical” pattern of a phrase can be misinterpreted or not understood at all. Nevertheless, such languages exist, which means they work.

Is it ancient?

You listen to how people can burst into a nightingale, and you think: maybe this whistle is the parent language, the ancestor of all Indo-European languages? Maybe people originally sang like birds?

Well, the fact that all languages have quite a few words that take their roots from onomatopoeia,

is a fact.

But all these “whistle signals” are built on the basis of already existing Spanish or Turkish, while these languages themselves did not originate from a single whistle. So, like any language-based code, whistling languages are secondary, they are not even restored-primary.

And one more thing to pay tribute: even birds and animals react to the Silbo Homero language! That is, it is interspecies communication. Which is also important in practice, when you need to call your sheep, but they no longer need human, but sheep’s words on a whistle.

Birds, on the other hand, probably want to make contact with humans for a long time.

It is known that the African honeyguide bird , which loves honey, but cannot get it out of the hive, chirps to a badger-honey badger or to a human and leads these mammals to a tree where honey, accessible to handy and legged creatures, which people use, is hidden and the animals can share with the bird.

Learn to whistle!

Whistling is a fairly good method of mastering the stress in words and the rhythm in phrases. And this is a great help in learning “ordinary” Spanish, Turkish or the Yoruba language.

Knowing the names of these whistling languages, you can search for materials on them ( useful links already contain some) or even travel to the country of the language being studied.

To everyone, striving his flight over the hills and mountains, not a fluff nor a feather !

Useful Links:

1) Silbo Gomero: El Silbo’s Mysterious Whistle Language – YouTube

2) Silbo Homero Learning Kit: Learn Silbo Gomero – become a Silbador! – Busuu

3) Kush Dili: Whistle Language Turkey – YouTube

4) Whistling language – Wikipedia (wikipedia.org)

5) Learn rare languages with Language Heroes! School of independent study of foreign languages - Language Heroes (lh22.

PictureCredit

-

Main Course: Rare Languages

6,000 RUB

Buy

Related tags:unusual languages rare languages

Whistler Island: how the unusual language of silbo homero appeared | lifestyle | 02/14/2022

The inhabitants of the islands of La Gomera and El Hierro in the Canary archipelago communicate with each other by whistling. Both islands are full of cliffs and steep slopes. Echoes in the mountains distort loud sounds, making it difficult to call each other, but whistling is ideal for sending messages over long distances. Silbo Homero – this is the name of this language – at the end of the 20th century was on the verge of extinction. The local authorities have solved the problem – now the whistle is taught in schools. Who came up with this unusual language? Why are they interested in intelligence agencies? And what other nations communicate by whistling? 9 talks about it0095 program “Mysteries of Humanity” with Oleg Shishkin on REN TV.

Silbo Gomero

Whistling is known to be a bad omen, but not on the island of Gomera. About 22 thousand people live here. On the neighboring island of Hierro, there are almost 11,000 more. In addition to traditional Spanish, all of these people can communicate using whistles. From a scientific point of view, Silbo Homero cannot be called an independent language; rather, it is a Spanish speech transposed into a whistle.

Photo: © Screenshot of video

Linguists still cannot answer the question of how the whistling language appeared, which the inhabitants of the islands communicate with. Blogger Ksenia Ilyinykh, the author of a documentary about the Canary Islands, believes that the Silbo language was invented by aborigines – the Guanches tribe.

“At the beginning of the 15th century, the Spaniards captured this island, and the Guanches, the locals, were already whistling to each other from one end of the ravine to the other. The Spaniards created a kind of hybrid of the Spanish language and the Guanche language. And still the locals whistle each other friend” , – said Ksenia Ilinykh.

Popularity of the language

Over time, this tradition began to annoy the colonists. In 1882, the mayor of the island’s capital, San Sebastian de la Gomera, banned Christmas services from churches. And all because the parishioners stubbornly continued not to hum psalms, but to whistle. And in 1906, the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII himself, granted the island of Gomera. He did not believe in the stories that the locals speak bird language, and decided to see for himself. The Monarch liked the language of Silbo.

Photo: © Video screenshot

“It was popular until the middle of the 20th century, but then it began to lose its significance, because it was perceived as the language of uneducated peasants.

The use of “bird language”

Modern technology has also played its role – why whistle when you can make a phone call? But in the middle of 9In the 1900s, the inhabitants of the island realized that a unique tradition was leaving their lives, which must be preserved. Since the late 90s, silbo homero has been taught in schools to children from the age of 11. The ability to communicate by whistling helps many islanders earn a living.

Photo: © Screenshot of video

“They attract tourists, especially in restaurants. Naturally, everyone applauds, clap, film it all on camera” , – the blogger noted.

It is not easy to learn the whistling language. There are six basic whistling techniques where one or more fingers are placed in the mouth.

In recent years, the Silbo Homero language has been adopted by representatives of the Spanish secret services. Communication with a whistle will help them negotiate in hard-to-reach mountainous areas where radio communication does not work. After all, the whistle is heard at a distance of up to 14 kilometers.

“The height of the whistle conveys vowels, and all the peculiarities of tone movement – up, down, intermittent – convey consonants. Any Spanish sentence can be reproduced in this language. It is clear that with some losses, therefore, of course, a lot depends on understanding here context” , the philologist explained.

“Bird Tongue” still helps the islanders in emergency situations. Two years ago, in the south of Gomera, at a fishing base, one of the workers badly injured his hand. A doctor was urgently needed, but no one at the base had a telephone.

Where else is whistling language

“Earlier it was believed that this island is the only place where the whistling language exists. But it is not so. It is found in some African countries, in Mexico, Greece, Brazil and many other places” , – said Ilyinykh.

Sefiriya is a whistling language spoken by the farmers and shepherds of the village of Antia on the Greek island of Euboea. In 2018, only six people remained alive who know Sefirian.

Photo: © Video screenshot

In Mexico, whistling is used to communicate in the market, and only men have the right to speak in this way. And among the Vietnamese Hmong people, the whistling language is used for flirting. Young men whistle poems on it when they want to attract the attention of girls.

“There are whistling languages in Alaska, so this is a fairly common phenomenon.

You can learn about the incredible events of history and the present, about amazing inventions and phenomena in the program “Mysteries of Humanity” with Oleg Shishkin on REN TV.

HOMERIC WHISTLE. Silbo Gomera and others

HOMERIC WHISTLE

Homeric whistle

>

A real sensation in the world of linguists and ethnographers was the study and even the “secondary discovery” of the already well-known “Homer’s silbo” of the Canary Islands. In 1957, Andre Klass, a teacher of phonetics at the University of Glasgow, spent three months with his wife comprehending the “basics” of this unusual language (Klass is now considered a recognized authority in the study of whistling languages).

Further, it turned out that “Homer’s silbo” has a number of amazing features. First of all, the whistle of the Homers is unusually strong – in the local technique of performance, it sometimes spreads over … fourteen kilometers. In its own way, a record in this way of exchanging information! One of the travelers who visited the Canary Islands at the beginning of the 20th century told a local anecdote about some incredulous Englishman who asked a Homer to test the strength of the sound by whistling in his ear.

In order to better understand the power of the “Homeric whistle”, it would be appropriate to give the following explanation. The power of the whistle of the Pyrenean highlanders from Aas, and they whistle “only” 2-3 kilometers, at a distance of one meter from the “whistle”, is, as noted by the sound counter, 110 decibels. What it is? A decibel is a unit of sound or noise power: 40 decibels is a normal conversation, 80 decibels is a sound that is difficult to bear, 120 decibels is a sound that can injure the brain … Indeed, the Pyrenean highlanders or the inhabitants of Homer’s island could measure themselves with the legendary Nightingale the Robber of Russian epics , in the image of which, perhaps, some vague memories of the “whistling” forest tribes that once lived in the Murom forests in Russia were also reflected. Who knows?

But let’s get acquainted with the testimony of an eyewitness who lived for some time on the island of Homer, in order to find out in more detail about the champions in such an unusual way of communication.

– Before you have time to go ashore, you already hear a lot about the language of whistling, – one of his acquaintances prophesied to the traveler in Las Palmas, the capital of the island of Gran Canaria, the most famous of the group Canary Islands. According to her, she knew Homer’s island well and was always surprised by the phenomenon of his whistling language. She also told the traveler that the coast of the island is so steep that new arrivals are lifted directly from the deck of the ship in a special cradle.

“To be honest,” writes Wustman, “we landed without a crane, and apparently it never occurred to anyone to inform the islanders of our arrival with the legendary “Homeric whistle.” Two taciturn islanders shouldered our suitcases, and we walked on foot to San Sebastian, the main city of La Gomera. But, according to the reports of travelers who visited the islands, everyone whistles on Homer – from young to old.

Indeed, this is a correct observation. Once in the mountains of Gomera, in the forest, the Klass spouses, who were studying the whistling language of the islanders, heard Spanish names whistling: “Felippe! Federico! Alfonso!” And for many miles, as it turned out, there was not a single living soul. The perplexed Klass did find the whistlers, blackbirds, songbirds from the “mockingbird” family, which perfectly imitated the human names they often heard in the forest.

As Wustman later found out, even the old Spanish and Portuguese chronicles of the discoverers (and the Canary Islands were discovered several times, starting from ancient times!) , and other Canary Islands in a moment of danger. According to local legends, each page of the history of the island was transmitted by means of a whistling language high into the mountains and from there again reached the farthest bays on the shores of Gomera.

The ancient inhabitants of the islands, the kind, blue-eyed giants of the Guanches, communicated with the help of the whistle language, fighting off heavily armed detachments of the Spaniards until they were completely exterminated, and the details of this tragedy were carried by the echo of the whistle to all corners of the island. It is said that with the help of the language of whistling, the rebellious islanders agreed on a joint action when they rebelled against the heavy exactions and ferocity of the Spanish conquistador governors; the men of the island, apparently already speaking Spanish, were whistled when the ships of the daring pirate Drake tried to attack the capital of the island, the city of San Sebastian.

A few years later, the islanders again whistled the alarm when the ships of the Dutch Gueuses decided to strike back at the Spaniards, avenging the burnt cities and villages of Flanders. The alarm whistle “prepare for battle!”, “To arms!” resounded over Homer when, in the 17th century, Algerian corsairs, having landed in the bay of San Sebastian, set fire to the captured city from several sides.

One of the most popular folk legends on the island of Gomera ascribes the invention of the whistling language to criminals and captives exiled here by the Spaniards in the Middle Ages. As if, according to the then manner of treating prisoners of war, their tongues were cut off in order to exclude the possibility of their conspiracy and escape from the island. And that these unfortunates, in order to understand each other, created their own original language of whistling.

Now it is difficult to establish whether there is some truth in the ancient legend of the Canary Islands, but one thing is certain – the whistling language existed here long before the arrival of the Spaniards and the first conqueror of the Canaries, the Norman Jean de Bethencourt, who annexed the islands to the kingdom of Henry III of Castile. The learned monks who were with him on the campaign, according to the words of the islanders, wrote down this strange legend: “Homer is the birthplace of tall people who are fluent in the most wonderful of all languages. They speak with lips as if they had no tongue at all.

These people have a legend that they were not guilty of anything and were severely punished by the king, who ordered them to cut out their tongues. Judging by the way they talk, this legend can be trusted.” Another Spanish chronicler cites a different version of the legend: “They say that the people from the Canary Islands are the descendants of African tribes who rebelled against the Romans and killed the judge.

The legend of the “tongueless people” given by the German traveler and the Spanish chroniclers is unlikely to explain the appearance of the whistling language in the Canary Islands, although it probably contains some grain of truth – in a very distorted form. One thing is clear, that without a tongue a person cannot whistle, as the inhabitants of Homera do, for the tongue plays an important, if not the main role in whistling. “Tongue and teeth – that’s what forms the whistling phrases” Homer’s silbo “and in a similar whistling conversation of the Pyrenean highlanders!” – says one of the researchers of whistle languages, the French scientist Rene-Guy Busnel.

Thus, if this was actually the case, and which is very doubtful, by depriving the prisoners of their language, they were made absolutely dumb. There can be no talk of any “invention” of the whistling language here. At best, this legend contains some vague information, dating back to ancient times, that the first conquerors who put things in order on the islands decided to protect themselves by using a similar “surgical operation” against the recalcitrant islanders, faced with an already existing whistling tongue. However, more than one generation of linguists and ethnographers has been struggling with this riddle, connected with the emergence of the whistling language in the Canary Islands and the legends explaining its appearance…

Some authors write that only the old islanders speak the language of whistling in Homer, and the youth, they say, have not understood it for a long time.

Wustman was told about all this by the Homers, with whom he quickly became friends, showing great interest in the local whistled language (which, of course, the islanders could not help but be proud of!). With them, the traveler went to the mountains more than once, always making sure that the “Homeric whistle” had time to warn the islanders of his arrival.

Usually they do this, the Homers explained to him: they take the most skillful whistler and he whistles everything that needs to be told to the neighbors through the gorges and abysses that abound in the relief of the island. Perhaps that is why the language of whistling arose here, since it was born of an urgent need. After all, Gomera is a small island, obviously of volcanic origin, which is inhabited by about 35 thousand people; there is only one road on the island and many impassable “goat paths”, and the whole of it is cut up and down by wide and steep gorges, along the bottom of which roaring streams of water run. They are so noisy that they even drown out human voices, and in order to get to a friend on the other side of the gorge and talk to him, informing him of the latest news, it is better to whistle all this to him than to climb steep cliffs for hours. Not surprisingly, even today, the Homerians prefer not to storm the gorges, not to scream, tearing their throats in the hope of drowning out the roaring stream, and not to call the phone – this 20th century luxury item on the island – but to communicate using the language of whistles.

To see for himself the effectiveness of the whistling language, Woostman did a simple experiment. One of the Gomers went far into the mountains, while the other stayed with him and translated everything the traveler told him into a whistle. The following dialogue took place:

— Oh, Evaristo! (That was the name of the second Gomer).

— Oh, what? came the reply.

Then I strained, Wustman writes, and, straining all my imagination, came up with a task, and my guide, Jorge, whistled it:

– Oh, Evaristo, take off your shoes, climb a palm tree and drop a couple of nuts for our guest,

Evaristo, without hesitation, did everything exactly – for this he did not even have to look through the binoculars, which Woostman had prudently brought with him : the air was clean and transparent.

Wustman was finally convinced of the universality of the whistling language by a little experience. One of his acquaintances from Homer Island whistled him a phrase in the local “silbo”, and he recorded it on a tape recorder.

Somewhere in the early 60s, the famous English writer and traveler Lawrence Green visited the Canary Islands. In his book “Islands untouched by time” (it came out with us at 1972) he gives a lot of interesting information about the whistle language in the Canary Islands. In particular, he writes, referring to the opinion of linguists who traveled on the island, that once the whistling language, before the Spanish conquest of the islands in the XIV-XV centuries, was much more widespread in the archipelago. He met on the island of Tenerife, on the island of Hierro – the most western and remote of the Canary Islands (the author himself also met him here) – and, apparently, on other islands. Lawrence Green, like Erich Wustman, also noted that many of the islanders speak the whistling language in the Canaries. In his opinion, this is not a lost art, but a generally accepted manner of speaking, and even small children own it, as he was convinced by doing, like any visitor, several experiments with adults and children.

The language of whistling, according to his stories, is still used on Homer for purely practical purposes. Thus, in the lower part of the city there is a pumping station that supplies water up to the tomato and banana plantations, and since the supply of water is accompanied by a number of complex operations, a real connection is maintained between the plateau and the pumping station using the whistle language. Further, one should not be surprised to hear lively and attractive, like the singing of a nightingale, the sounds of a whistle exchanged between a waitress in a cafe and a cook in the kitchen. So she whistles every order, every dish – from potato soup to pancakes with sauce. She can even tell you how the eggs should be cooked – soft or hard boiled, what kind of wine or coffee should be served. Moreover, as Green ironically, “when it comes to sweets, the whistle becomes, in my opinion, more melodic.” On the island, parents speak the language of whistling to their children, and even every child under the age of one raises its head, responding to its name.

It happens that a car breaks down somewhere along the way, and the driver whistles to someone, and he whistles further until the message reaches the nearest garage and technical assistance is sent to him. Fishermen whistle from boat to boat, reporting on schools of tuna, which the local waters have been famous for since the days of Carthage. And on ships unloading in the port, instead of the usual “main-vira”, a piercing whistle is heard. Since there is not a telephone everywhere on Homer, the whistling of the inhabitants of the island over the years, says Green, saved many people who urgently needed medical attention. So, when a doctor was urgently needed at the Kantera fishing base, which is located in the south of Gomera, alarm whistles were heard, and six minutes later the doctor in San Sebastian, the capital of the island, already knew about the accident – moreover, he was even told the symptoms of the disease: five men of Gomer, fishermen and shepherds, transmitted this message over a distance of more than nine miles.

Lawrence Green was told two comical stories about the practice of Homer’s silbo by the locals. One of them told about a local rich farmer who lived on the island half a century ago. The sharecroppers who worked on his plantations often deceived the owner, but they always had time to warn them with a “Homeric whistle” as soon as he went to check on his farms. Finally, the angry owner took lessons in the language of whistling and, on his next visit, managed, listening to the whistle, to compile a complete list of pigs and cows, goats and sheep hidden from him by the shepherds.

And the most famous demonstration of the whistling language on the island, according to the Homers, was in 1906, organized for the Spanish king Alfonso III. The incredulous monarch was dubious about reports of the local “silbo”, and two Gomer soldiers tried to convince him of the opposite.

For a beginner, linguists unfamiliar with the phenomenon of the whistling language say, all words in it sound the same, like one continuous vowel, but people who speak it can easily decipher the most complex phrases. The whistling language of the Homerians has its own peculiarities and conventions – after all, it is the language of whistling, and not pure “conversation”. For example, for some reason you can’t just whistle “January”, “February”, “March”, but you must definitely add the word “month”. Apparently, this is due to the fact that when transmitting a phrase over a long distance, when fingers are put into the mouth to get a sufficiently powerful whistle, the speech organs are partially constrained and the phrase in “Homer’s silbo” sounds illegible.

Researchers who have studied “Homer’s silbo” have made the most thorough analysis of this whistling language, which they consider “whistle Spanish” (or “whistled dialect of Spanish”). Unfortunately, it is rather difficult to give a popular presentation of their phonetic-linguistic conclusions, due to the complexity of linguistic terminology, since they are of a purely scientific, narrowly specialized nature, understandable only to professionals. However, researchers believe that getting a whistle in “Homer’s silbo” is much easier than forming normal conversational speech.

The limited meaning of the transmitted messages, stress, rhythm and intonation of whistling phrases, “key words”, having heard which the partner understands approximately what the message will be about, is also important in “Homer’s silbo”. By the way, according to linguists, this indicates that Homer’s “silbo” is degrading and actively falling into disuse. Probably, before it was possible to talk about anything, although even then there were certain limitations in the language of whistling: it was possible, apparently, to convey specific information (and not abstract concepts), that is, to conduct a conversation on “abstract topics”.

Naturally, the tongue, lips, teeth, and fingers play the most active role in the formation of the whistling language. Their various positions and combinations make it possible to build certain whistling phrases on Homer’s silbo. In this case, the oral cavity, bronchi and lungs act as a kind of resonator that amplifies the sound. “In ordinary colloquial speech,” one of the researchers of Homer’s “silbo” wrote, “we distinguish the constructions of words and phrases, and not individual sounds, most of which are not perceived clearly, in “silbo”, on the contrary, everything is audible, everything is legible … » According to another linguist, the indistinctness of ordinary speech when talking over long distances is associated with the loss of weak harmonic and non-stationary complex speech waves, while a whistling message, the meaning of which does not depend on timbre, but is entirely determined by the pitch, will be clearly understood within the whole conversation. That is why “silbo” has become a convenient system of long-distance communication among some peoples of the globe.

It is difficult to say why the Canary Islands did not invent something more suitable: like African drums – tom-toms or slotted “talking” drums – tuddukats, which are still preserved in Africa and Melanesia. Maybe they were simply “not thought of” here (although there are tom-toms in West Africa, there is also a whistling language) and the whistling languages of the world are actually the most ancient remote “intercom” that is “always with you”? Older than any other mechanical device for transmitting messages over long distances…

It is interesting to compare the “language” of the slit tuddukat drums known to ethnographers from the island of Mentaway (Indonesia) with the whistling information transmission system. Thus, the inhabitants of the island believe that tuddukat signals sound to them like ordinary speech, and not like sets of conventional signs conveying a particular message. Indeed, Mentaway’s drums are tuned to transmit individual sounds of human speech, despite the fact that Mentaway is not a tonal language. Here’s how it works in practice: each drum is associated with certain vowels: 1st – with i, u, ui; 2nd – with e, o, ei, eu, oi; 3rd – with a, ai, au, etc. Separately pronounced, following one after another, vowels correspond to only one drum beat. So, for example, the word “maruei” (quickly) is conveyed by drum beats 3-1-2, which corresponds to the vowels in the syllables “ma-ru-ei”. Texts that should be transmitted to a neighboring village are compiled and rhythmized by the Mentavians in advance, adapting to the tonality of such an unusual “telegraph”, which, really, is the pinnacle of the development of a drum information transmission system. She, according to researchers, stands completely apart in Asia and Oceania and is not found anywhere else. Scientists attribute its origin to the Neolithic of these regions of the world, when such an amazing art of the “drum language” was born, somewhat reminiscent of the “silbo” systems among other peoples of the world …

Or maybe just the opposite: the language of whistling originated from the language of drums and other sounding devices, being a higher stage in the development of means of information exchange? Unfortunately, the comparison of whistling languages in the most diverse regions of the world with the language of drums in the same regions of the world has not been carried out by any of the linguists. Perhaps this comparison contains the secret of their origin, the pedigree of each of them, the connection with each other, the answer to the question: what is next – a whistle or a meaningful drum signal?…

how to learn the most difficult languages in the world

Interesting ideas /

Incredible Facts

Learning Japanese and complaining about three different alphabets? Have you started English? Good luck! Every language has its own difficulties. However, our five is real hardcore…

Place No. 5. Archa is a language with 1.5 million verb endings

There are three different verb endings in English. Namely: -ing, -ed and -s. Until everything is clear? Excellent. In the Archa language, the language of the indigenous people of southwestern Russia, there are 1,502,839 verb endings. Think about it for a moment – a native Archin speaker can send you in more ways than there are words in the Oxford Dictionary.

In addition to the tense form, the Archa language has many verb modifiers for gender (there are four in the language, they are progressive), case, number, and a lot of grammatical nuances that are not in English.

Therefore, saying, for example, “He farted”, a native speaker of Archi can say who exactly did it, when, how many there were, express the degree of confidence that this particular action took place, how loud it was, describe the conditions under which this incident happened and even how bad the smell was all accompanied by – and all this, just a slight change in the verb. Therefore, by the time you can figure out how to say in Archin so that the villain stops spoiling the air in the car, there is a high probability that everyone in this very car will have time to be poisoned by methane.

Place No. 4. Silbo Homero – whistling language

Silbo Homero is spoken by the people of the Canary Islands and is the easiest language on our list. Its “alphabet” consists of only two vowels and four consonants. We have finally found a culture that values simplicity! However, if you want to speak it, you’ll need keen ears and incredible breath control, as silbo homero is a language that is articulated entirely by whistling.

The modern language is a variation of the language of the African tribes that once inhabited the island. The Canary Islands fell under the rule of the Spaniards, who practically wiped out the local population, since imperialism was planted in this way. However, the Spanish settlers were fascinated by the unique way of communication of the local population and adapted it to their native language and still take it seriously – whistling is a compulsory part of the school curriculum.

Silbo gomero is a complex enough language with its own nuances that whistling can be used to convey news and holiday announcements over long distances. The local farmers of the islands could hear the skilled whistler from two miles away, which was perfect for the region’s mountainous terrain. If you are working at the top of a ravine and suddenly notice a rake trailing behind your wife, who is a mile away from you, you can explain in detail, but at the same time very melodiously, how you will kick his ass.

Place No. 3. Khong is a click language with 122 consonants

Khong is spoken by about 3,000 natives of Namibia and Botswana in Africa. While speakers of English and other European languages use only 26 letters, the Khong language has 122 consonants alone. This is because this language uses many more sounds than others.

It is similar in pronunciation to Chinese, if it were spoken while chewing gum and playing ping-pong. However, all those smacking, clicking and crackling sounds have many meanings. There is no written alphabet, and most sounds don’t even have a rough equivalent in our language, so linguists have to resort to all sorts of fancy symbols to transcribe what they hear.

Linguists claim that Khong, or its equivalent, may be the oldest language in the world. When we immigrated from Africa, our way of communicating changed radically and almost all of the ancient clicks were lost.

Seat #2 The Pawnee, a language where words are put together like in LEGO

The Pawnee, a tribe of Native Americans from central Oklahoma, speaks a polysynthetic language in which words are formed by gluing different components together in this way that a complete, complex thought can be expressed in a single, carefully supplemented word. For example, “Hatkaahuhtiirahpuh” means “to dig a small trench or ditch around the perimeter of a dwelling to prevent water from seeping in, or around the perimeter of a yard to avoid a drain.”

Seat #1. Tuyuka is a language with 140 genders